The Avoidable Tragedy of Low Hospital Capacity in New York City

Working Paper Series on Corporate Power: Paper #3

Introduction

Weeks ago, New Yorkers broke social distancing rules to gawk at the arrival of the USNS Comfort, the Navy hospital ship brought to the city to address the overflow of coronavirus patients. The temporary surge in capacity is essential; without it, the fragile New York City hospital system is at risk of watching patients die without receiving care.

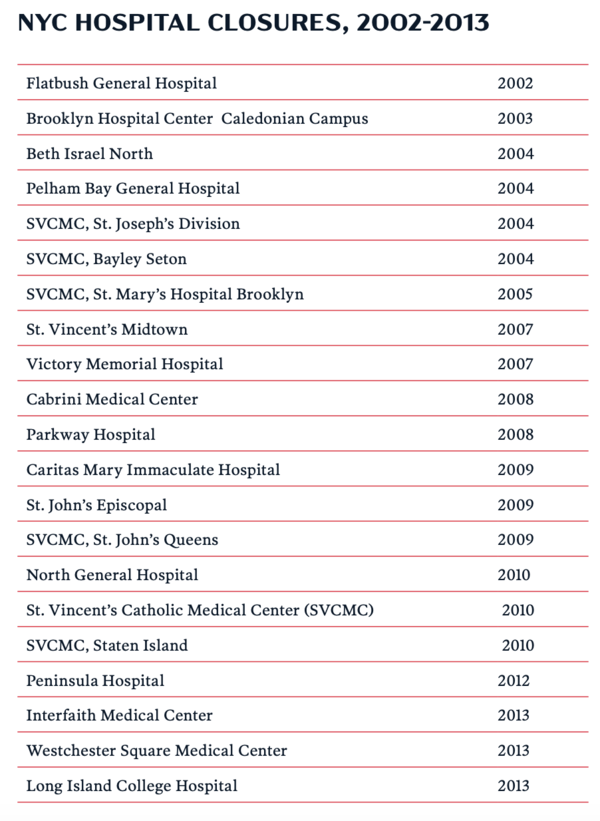

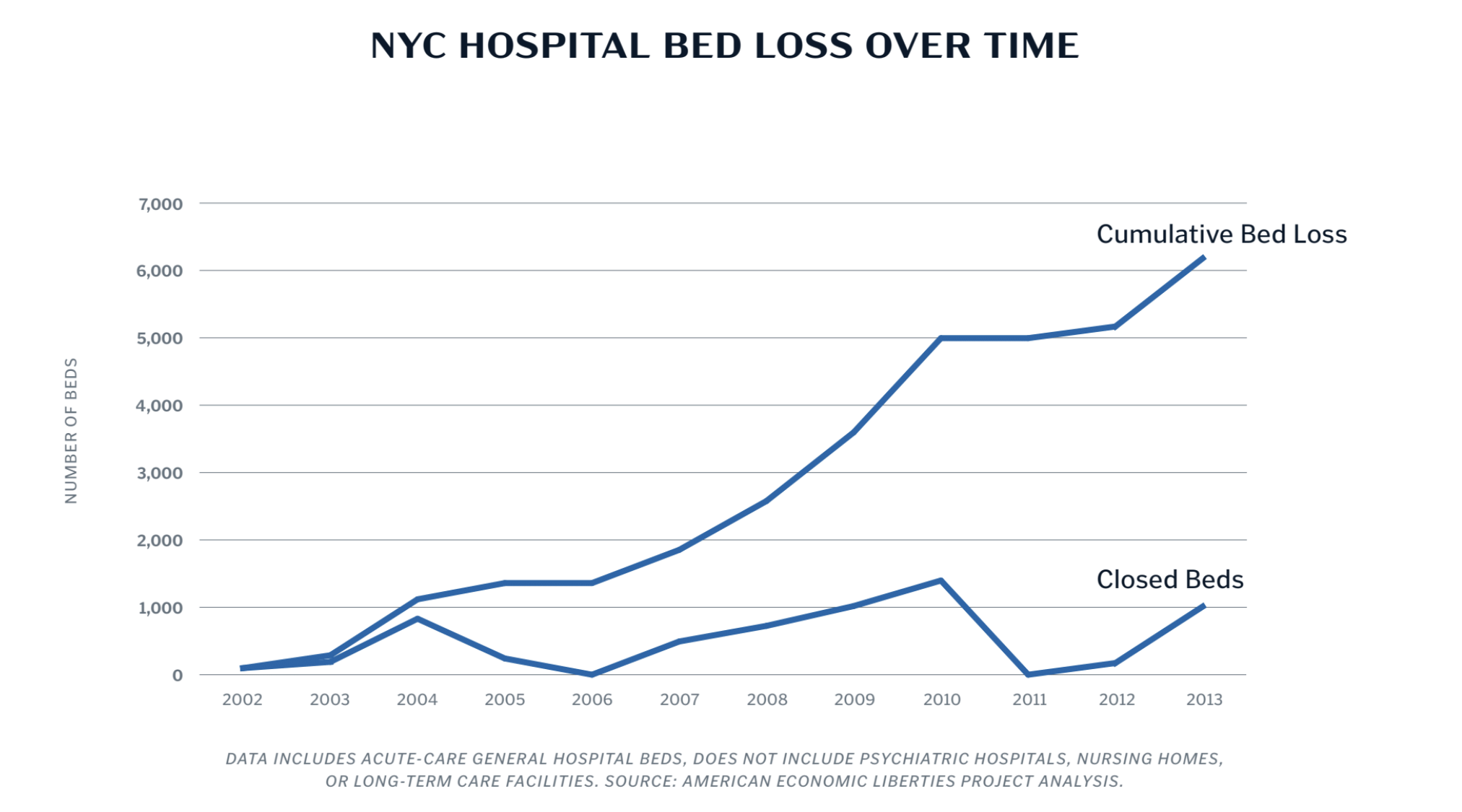

The NYC health system used to be much stronger—and better prepared to respond to catastrophes—until it was weakened by deliberate policy choices that prioritized cost savings over preparedness. From 2002 to 2013, New York City shuttered at least 22 hospitals with more than 6,000 beds between them. The loss of those hospitals represents the capacity of at least six USNS Comfort ships.

Not only did the hospital closures weaken the city’s responsiveness to disaster, they also didn’t have the intended effects: instead of going down, health care costs skyrocketed. While health care costs have risen dramatically across the country, New York State managed to surpass the national average. The high costs of drugs, physician visits, and—despite closures—hospital care pushed per-person spending up more than 6.2 percent annually in New York State compared to a national average of less than 4 percent from 2013-2017.

When officials closed hospitals, they took aim at the wrong problem. The real driver of cost in the American health care system isn’t excess capacity, but consolidated power. Simply put, we pay more to monopolists for medicine, drugs, supplies, and hospital inputs than anyone else in the world. And rather than cutting the fat of inflated prices, New York City cut bone: the beds we need to keep people alive.

***

These trends aren’t limited to New York State. By 2016, unprecedented numbers of hospital mergers across the country resulted in 90 percent of metropolitan areas being highly consolidated. These highly consolidated health systems are able to charge monopoly rents.

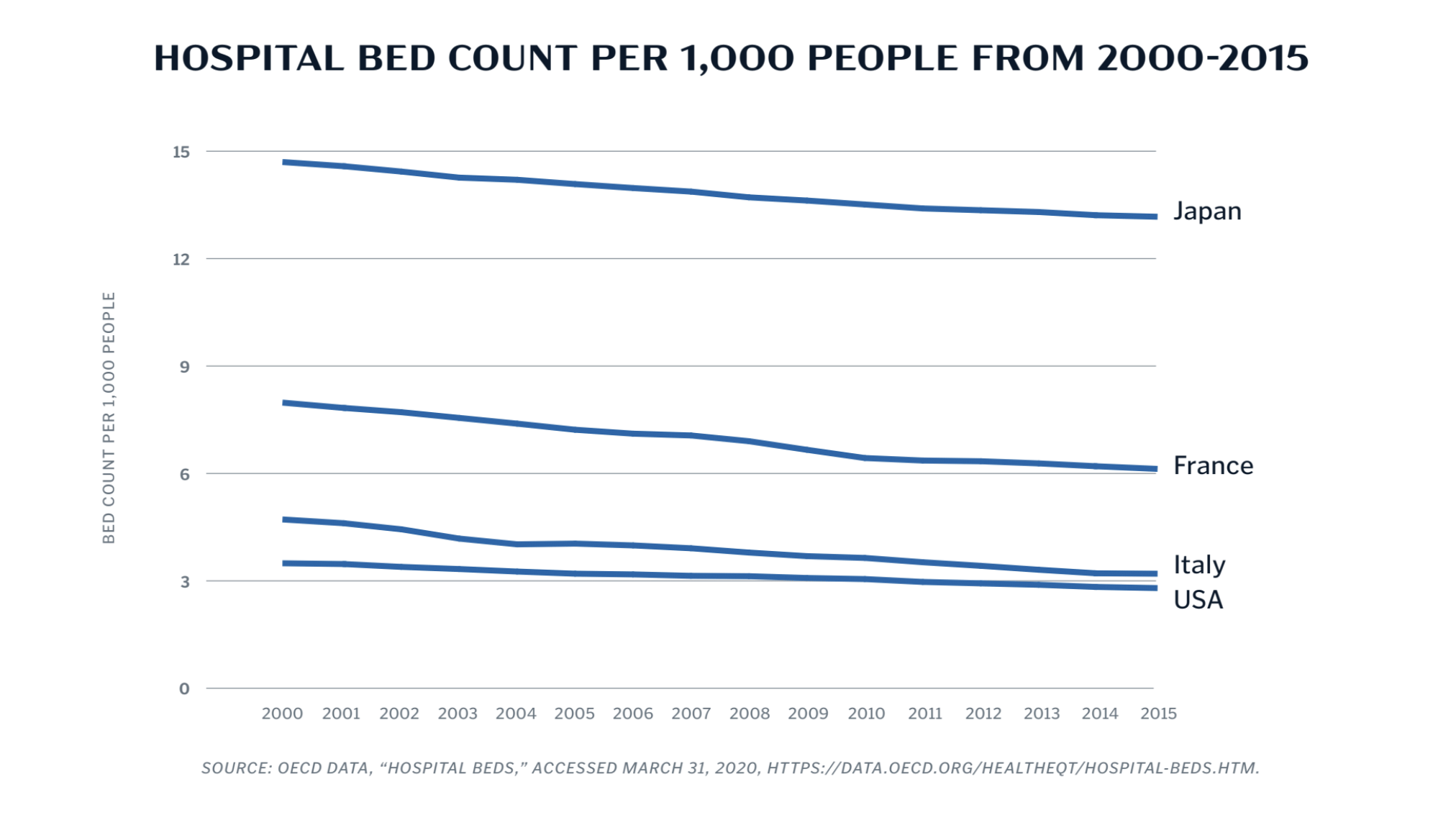

Rising prices aren’t limited to hospitals; consolidation in the pharmaceutical, medical device, and hospital supply chains have contributed to cost increases throughout the industry. And these rising prices have cascading consequences. Namely, smaller community-focused hospitals often can’t keep up, and local officials allow them to merge into larger systems or shutter for good. Overall, the number of hospital beds in the U.S. has fallen from 3.5 hospital beds per 1,000 people in 2000 to 2.8 in 2016. Now, the U.S. has far fewer hospital beds than most other OECD countries, including those overwhelmed themselves by the COVID-19 pandemic.

By not addressing the root causes of high costs, lawmakers have allowed U.S. health care costs to inflate to some of the highest in the world. As a percent of GDP, the U.S. spends far more than any other OECD country: nearly 17 percent compared to roughly 11 percent in Germany or Canada. At the same time, Americans only visit a physician four times a year on average, compared to seven average visits across the OECD. In other words, people in the U.S. pay a premium for the privilege of lacking physicians, beds, ventilators, and drugs during a crisis.

The hospital closure crisis is likely to continue, unless lawmakers step in. Hospitals make most of their revenue from elective procedures rather than ICU care. With the pandemic driven cancellation of elective procedures, hospitals and staffing companies are furloughing or cutting pay to essential medical workers.

As medical technology and research advances, the U.S. may indeed require fewer hospital beds. Those decisions, though, should be made on a public health basis, rather than a cost-saving basis, especially when the system is marbled with monopoly rents that could be addressed through policy and regulatory choices.

Solutions

What can be done? Lost beds cannot be returned instantly. Instead, as the pandemic sweeps across the country, lawmakers must support existing hospital capacity, especially community hospitals and independent doctors’ practices. Then, they should turn to long-term strategies to address the concentrated power of the health care system.

PRESERVE CURRENT HOSPITAL CAPACITY BY SUPPORTING HOSPITAL BUDGETS

We must save what we have before we build on it. There are a few options available to policymakers to ensure the preservation of existing capacity. The more radical option is adopting Spain’s strategy: executing a temporary public takeover of the financing of hospital systems. In other words, this option would transition hospitals to a global budgeting system handled by the Department of Health and Human Services. Hospital administrators would be able to send their billing and fundraising staff home temporarily (while continuing to pay them), and patients would be treated free of charge. Simultaneously, federal funding would support hospitals in buying adequate PPE and ventilators, as well as covering payroll for the duration of the pandemic.

The more moderate option involves Congress capping hospital and physician practices at Medicare rates across the country, while assisting hospitals with the high costs of fighting the pandemic. This would keep costs low, allowing the insurance industry to fund care at reasonable prices (and stanch the projected 40 percent jump in insurance premium prices). As part of this policy, Congress should also ban surprise billing—in this case, billing beyond Medicare rates. Patients should not have to pay for care during the pandemic, and corporate interests behind high hospital and drug costs should not profit from this catastrophe.

PROTECT COMMUNITY AND INDEPENDENT MEDICAL PRACTICES FROM CONSOLIDATION

The pandemic could also have dire outcomes on the long-term flexibility and capacity of the national health care system. Without the ability to perform the elective procedures that comprise a significant portion of their revenue, community hospitals and independent doctors’ practices are at high risk of being forced into mergers with larger systems to stay afloat during the crisis. Smaller, independent facilities are the lifeblood of community health care, and they are often the cheapest, most mission-driven option available. The loss of these institutions would be a devastating addition to the coronavirus toll.

Community practice advocates have already expressed concerns that the CARES Act prioritizes large, corporatized hospitals over smaller entities; federal and state governments should ensure that small entities also benefit from the money available. Solutions may involve a specific pool of funding for community, non-merged entities, or entities that can show they provide a disproportionate share of cheap, community-focused care. At the very least, the hospital funding provided by the CARES Act—and subsequent money directed toward hospitals—should be distributed in a way that does not punish hospitals for not keeping consultants on perpetual retainer.

STOP PANDEMIC-PROFITEERING BY PRIVATE EQUITY

Hospitals and medical practices owned by private equity companies are also vulnerable to closure, but not exclusively for lack of funds. In at least a few instances, private equity owners are leveraging their hospitals to extract more money. The private equity company that owns Easton Hospital in eastern Pennsylvania, for example, threatened to shut down the hospital unless they received more state funding. The private equity owner of the former Hahnemann University Hospital in Philadelphia—who purchased and shuttered the once-functional hospital to sell the real estate under it—has held the (currently empty) building hostage, refusing to sell it to the city save at exorbitant rates. Short-term, lawmakers should consider leveraging eminent domain takeovers for hospitals that are uncooperative and risking public welfare. Long-term, Congress should consider a ban on private equity ownership of health care entities.

BREAK UP THE CONSOLIDATED HEALTH CARE INDUSTRY

These potential legislative options do not take into account an important concern of health care policy: rising costs throughout the system. If the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated anything, though, it has shown that shuttering health care infrastructure is a painful and unsuccessful way to address costs. Lawmakers should address the long-term expense that consolidation imposes on our health care system.

Under the current system, pharmaceutical companies can charge exorbitant prices for new drugs that they protect from competition under a pile of patents. Insurers, pharmacy benefit managers, and retail pharmacies continue to consolidate into large, vertical systems with opaque pricing. Large “power buyer” purchasers force hospitals into sole-source contracts and drive smaller manufacturers out of business. Huge hospital systems with geographic monopolies are free to charge ever-increasing hospital prices that insurers and patients are forced to cover, lest their wages be garnished. The private equity owners of some physician staffing groups, especially in emergency care, keep their stock prices high by charging large surprise bills to patients in excess of what their insurance is willing to cover.

Policymakers and enforcers should undertake wide-ranging investigations into the concentrated drug, medical device, and hospital industries, as well as the concentrated purchasers that provide hospitals with those materials, with the goal of guiding the restructuring of these markets so they are aligned with public health and well-being. Lawmakers and the regulators of the FTC and the FDA should consider unrolling approved mergers—for example, the CVS/ Aetna merger of 2018—and policing the anticompetitive practices of the group purchasing and pharmaceutical industries.

In some markets, it may be unfeasible or undesirable to break up the industry into smaller pieces. In such markets, policymakers should use tools like price caps or public manufacturing, constraining costs even after the pandemic ends. This should extend to hospital charges, outpatient surgery charges, and off-patent drugs like insulin.

Conclusion

For decades, we have allowed hospital mergers and closures without protest, trading short-term costreduction efforts for long-term fragility. Every life lost to coronavirus is a tragedy, but American deaths from a lack of hospital beds are an indictment on our current system. It is long past time for policymakers to learn the lesson the pandemic is forcing us to confront: consolidation drives cost increases and weakens our ability to respond to crises. Confronting this power is the only path forward.

Appendix