Close to Home: How the Power of Facebook and Google Affects Local Communities

By Pat Garofalo

Since 2016, commentators across a swath of disciplines have pointed to Google and Facebook as consequential and harmful actors in the global political and social order. These platforms influence world events by doing everything from disseminating fake news during national elections[1] and a pandemic in the U.S. and abroad[2], to helping hate groups form and organize[3], to aiding in the fomenting of genocide in Myanmar. [4]

One area often missing from the discussion, though, is the corporations’ impact on local communities, both through their products oriented to organize local social and economic life and their corporate strategies around taxation.

Yet local strategies are core to both platforms, and while policy can be done at a national level, life is lived locally. The shops, businesses, public spaces, schools, and people around us make up our neighborhoods, and the taxes we pay support our communities.

Indeed, Google and Facebook know this, and portray themselves as organizers of local communities, helping connect people to the small businesses and neighbors around them. “One of the biggest opportunities is to help small businesses create connections with customers in their local neighborhoods and beyond,” Google CEO Sundar Pichai wrote in October 2019. “While the internet has given people the ability to buy anything from anywhere, often they are searching for what’s right next to them: the closest pediatrician, the best pizza delivery in Omaha, a hair salon open today.”[5] Pichai said this is especially true during the coronavirus pandemic: “Definitely we see activity back around people trying to find services, what’s around, what’s open. People are exploring and discovering local services again.”[6]

Similarly, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg has touted himself as a “community builder,” likening Facebook groups to “churches, sports teams, unions or other local groups.”[7] Through 2017, Zuckerberg had discussed “community” 150 times in public[8]: “Meeting new people, getting exposed to new perspectives, making it so that the communities that you join online can translate to the physical world, too,” is a Facebook goal, he said.[9] On calls with investors, Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg routinely talks up the importance of Facebook for small and local businesses. As Zuckerberg once indelicately put it, “A squirrel dying in front of your house may be more relevant to your interests right now than people dying in Africa.”[10]

And yet, when looking for local news or community information on social media, you don’t necessarily get the most trusted or professional sources, or those from traditional community stakeholders such as newspaper editors, local business, unions, or religious leaders — you get what Facebook wants you to see. When you run a Google search to find a local restaurant, you don’t necessarily get the best or most useful information — you get what Google wants you to see. When attempting to access information about where your local government is spending local resources or what it is charging for utilities, you often can’t get the full picture, only a snippet that Facebook and Google will allow. And when paying your local taxes to support your community, you may not realize the money is often going to subsidize the businesses of Google and Facebook through tax concessions hidden via shell corporations.

The net effect undermines the ability of locals to access good information; instead, the vacuum is filled by commentary and conspiracies.

For instance, in Holyoke, Massachusetts, the loss of several local papers resulted in the town having just one newsweekly that does no investigative reporting. When a ballot initiative in 2019 that would have OK’d a bond issue for two new middle schools was put forward, commenters in a local Facebook group spread misinformation about the city’s finances, such as who would be responsible for any potential cost overruns on the project. Targeted advertisements against the initiative were run by a committee[11] whose largest funder was the local mall, the largest taxpayer in the city.[12] The ballot issue was ultimately defeated.[13]

Regardless of the merits of the measure, a dedicated local news outlet would at least have been able to provide accurate information regarding the state of the city’s finances and its ability to cover the cost of the schools. Instead, as one city employee put it, local government officials wound up “playing whack a mole with every little conspiracy theory out there.”[14] The city simply wasn’t equipped to run a propaganda campaign on behalf of funding schools.

This policy brief will examine Google and Facebook’s effects on local communities in two ways. First, it will examine the impacts of their product lines: How their search and social networking services affect local communities through their organizing of advertising markets and the viability of local journalism. Second, it will explore more direct political strategies by these corporations to extract subsidies from local communities, and how they hide what they are doing from voters. These are surely not the only harms the corporations inflict on local communities, merely some of the most egregious.

Finally, it will detail solutions – at both the federal and local level – to readjust the legal underpinning of the platform business model, so that Facebook and Google’s strategies of self-preferencing to exclude competitors and profiting via misinformation are no longer viable, and so that local communities can prioritize small businesses and local services over the business imperatives of these extractive giants.

What Are Facebook and Google?

Popularly portrayed as big tech companies, Facebook and Google – and the other properties they own, such as WhatsApp and YouTube, respectively – are better understood as vital 21st century communications networks.[15] They’re the platforms on which local shops and restaurants connect to customers, on which local news is disseminated, and on which citizens organize everything from school bake sales to local elections to neighborhood clean-ups.

But their business models are not based on serving consumers with the most credible information and facilitating neutral communications among friends, family, and community stakeholders. Instead, Facebook and Google use intrusive surveillance of their users to collect data, and they use algorithms based on “engagement” to ensure users continue to pay attention to curated content. They then sell user attention, enriched with data, to advertisers, often monetizing content they didn’t generate but are profiting from, with users manipulated into further engagement with their properties. Both companies have incentives to self-deal and self-preference their own content in order to capture market share, and then use engagement algorithms to sell more advertising.[16]

Good information isn’t what Facebook and Google are selling. You are being sold to advertisers through what you see and interact with.

As tech reporter Rani Molla put it, “This business model has been around for decades, and it shows how free software (not to be confused with the free software movement) and services are never really free. You’re paying with your data.”[17]

How Dominant Search and Social Networks Affect Local Communities

Google Undermines Local Businesses:

For a local business to operate and be successful, local residents must be able to find it. There’s a long history of enabling such matchmaking between customers and businesses through newspapers, radio, TV, directories, and local advertising channels. Today, one of the key mechanisms filling this critical function is local search. Local search is the single largest category of search on Google, the world’s dominant search engine. In 2018, Google said local search grew by 50 percent over the year before, outpacing the overall search market.[18] More than 80 percent of cell phone users report searching for businesses “near me.”[19]

And yet, Google’s search properties, either general search or via its Maps subsidiary, often hurt local businesses and residents by allowing scammers to infiltrate its listings. For instance, Florida locksmith Rafael Martorell explained that the name of his business, A-Atlantic Lock and Key, was stolen by scammers on Google who pretended to be him and would charge customers five or six times what he normally charged. “One of the scammers put the name of my company, and the address that he put was my own house,” he said, alleging that such practices are an epidemic in the locksmith industry.[20]

“90 percent of our advertising, most of that for years was the Yellow Pages,” Martorell said. “Then suddenly Google came, without us noticing. And then we figured it out, we knew we had to go to Google and that is when the issues began. Because the local listings, most of them are fraudulent. Completely phony, fraudulent.”[21] The Wall Street Journal noted several other sectors in which similar scams have occurred.[22]

Since Google is so dominant in search, merchants have little alternative to battling the corporation endlessly, trying to buy ads for which they can’t ascertain the true value – and where a substantial amount of clicks can be fraudulent[23] – or simply vanishing from the vast majority of internet searches when they are either not listed or when their listing has incorrect information. (Facebook can create similar issues for small businesses via fraud, driving up costs for businesses running ads and opaque algorithm changes that limit small businesses ability to ensure their customers actually see their content.)[24][25]

Google’s size and scale leads to neglect of local needs. The corporation has eight products with more than a billion users, so the ability of a top executive to focus on any one town, or even a major city, is virtually nil. Google is slow to correct misinformation and has allowed whole neighborhoods to be renamed thanks to user mistakes. In other instances, Google has decided that an entire sector of the economy, such as third-party tech repair shops, is simply too difficult to validate, so it excludes them from search results entirely.[26]

Google’s power is immense, and in some ways, more significant than that of the government. As one businessperson told the Wall Street Journal, “if Google suspends my listings, I’m out of a job. Google could make me homeless.”[27]

Poor-quality results can even be profitable for Google. Legitimate businesses often pay for ads on Google in order to rise back above fraudulent listings. Martorell, for instance, spent $115,000 on Google ads between 2008 and 2015, before giving up on the platform and relying on local referrals.[28]

Local search is not an inherently concentrated business. There are competitors, such as Yelp, TripAdvisor, and other specialized vertical search engines that can compete over quality. And yet Google is a virtual monopoly. That’s because dominance didn’t occur naturally or through differentiating based on quality. It happened through the exercise of power and capital.

For example, Google pays to be the default search option on Safari on the iPhone. Google also provides its Android operating system and its app store Google Play to cell phone makers for free so that they make Google search the default on Android phones.[29]

This search dominance also allows Google to preference its own products providing local information over those of its competitors, even when its own organic search results indicate that Google content is of worse quality.[30]

Google’s search results have evolved over time. While the company once simply provided a list of hyperlinks to other websites, saying that it’s goal was to get consumers into Google and then out to their preferred web destination as quickly as possible, it now provides answers to specific queries and makes suggestions for content that can be accessed through Google directly, through its use of information boxes.

These include answers to factual questions, like offering that Thomas Jefferson was the third president without having to send the user to an online encyclopedia. But these boxes also allow Google to make a judgment call to preference its own content and products in harmful ways.

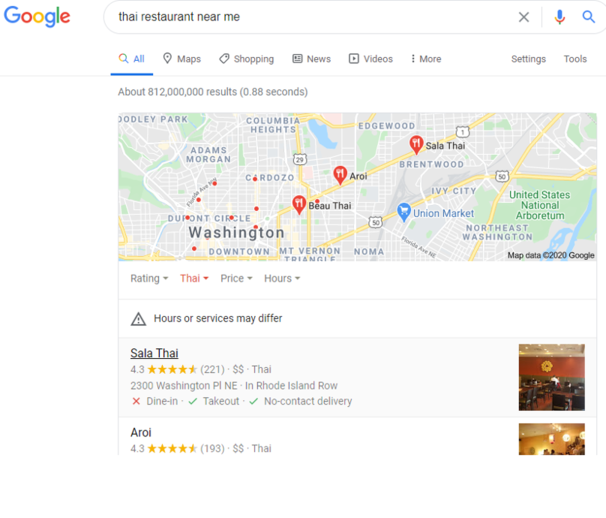

For example, a search for a local Thai restaurant will provide links to restaurant websites, but above the hyperlinked search results Google provides direct links to restaurants on Google Maps and Google’s restaurant reviews, as shown below:

Placement on a Google results page is critical because more than a quarter of users click the very first result of a search, while just 2.5 percent click on the tenth. Barely any users venture onto the second page of results.[31] As of 2019, less than half of Google searches result in a user clicking away from Google.[32]

Google’s ability to exclude competitors leads to the quality degradation in results, and so users end up more susceptible to fraudulent listings than they would otherwise, undermining the relationship between local businesses and local customers.

As one study on Google’s self-preferencing noted, “The easy and widely disseminated argument that Google’s universal search always serves users and merchants is demonstrably false.”[33] The European Union in 2017 fined Google €2.4 billion euros for similar self-preferencing of its Google comparison shopping products, which it placed above those of other third-party sales platforms or direct vendors.[34]

According to at least two studies, users prefer the content that Google’s algorithm would naturally show them to that shown when Google circumvents its algorithm to preference its own content. In 2015, Michael Luca, Tim Wu, Sebastian Couvidat, and Daniel Frank found that users are 40 percent more likely to engage with local search content produced by Google’s organic algorithm than they are with the content Google instead preferences in local search. (Yelp, a Google competitor, provided funding for the study.)

“Google is degrading its own search results by excluding its competitors at the expense of its users,” they wrote. “In the largest category of search (local intent-based), Google appears to be strategically deploying universal search in a way that degrades the product so as to slow and exclude challengers to its dominant search paradigm.”[35]

In a 2018 paper, Luca and Hyunjin Kim also found that users preferred organic search results to Google’s preferenced results. Furthermore, they found that other, more specialized search engines saw a fall in traffic as a result of Google’s actions tying its reviews product to its search engine.[36] “Our findings suggest early evidence that dominant platforms may, at times, be degrading products for strategic purposes, such as excluding competitors in adjacent markets that they are looking to enter or grow in,” they wrote.

The Federal Trade Commission in 2013 concluded that such behavior was anti-competitive, though it closed the investigation without action. According to documents from that investigation that were accidentally leaked to the Wall Street Journal, Google engaged in this conduct because it feared competition from specific search verticals such as Yelp and TripAdvisor. One executive in an email explicitly pointed to the threat such specific verticals posed to Google’s traffic, and therefore revenue.[37]

An inability for customers and local businesses to find each other, whether because there are too many scam listings to wade through or because Google is pushing an inferior product, hurts local economies – first, by potentially driving legitimate businesses under via depriving them of customers, and second by exposing customers to fraudulent businesses charging excessive rates. Changing Google’s business model so that it doesn’t have incentives to self-deal or tolerate scam artists will begin to rectify these problems.

Facebook and Google Undermine Local News:

According to the Save Journalism Project, 32,000 newsroom employees have been laid off in the last 10 years. 1,300 communities have lost local news coverage in the last 15 years. 60 percent of U.S. counties have no daily newspaper and 171 counties have no newspaper coverage at all.[38] Significant outlets such as the Denver Post, the Columbus Dispatch, or the Fayetteville Observer, along with many others, have been acquired by financiers who gut newsrooms and consolidate publications in order to squeeze whatever remaining capital there might be out of the newspaper business.

This decline in news coverage has had several deleterious effects on local governance and commerce. First, it lowers democratic participation, as regular newspaper readers are more likely to vote.[39] Areas that lose their daily newspapers see fewer candidates run for office, have incumbents win more often, and see voter turnout decrease.[40] One study found that staff cuts at local newspapers are correlated with less competitive mayoral races, fewer candidates entering races and more incumbent-only races.[41] Residents of areas with less local news coverage aren’t as likely to know the name of their member of Congress – and those members aren’t as responsive to their districts, bringing less federal money back.[42]

Lack of local news coverage also makes local financing more expensive.

According to a 2018 study, municipalities that experience a newspaper closure have higher borrowing costs in the following years, with the average bond issue costing the municipality an extra $650,000.[43] “Our evidence suggests that there is not a sufficient degree of substitutability between local newspapers and alternative information intermediaries for evaluating the quality of public projects and local governments,” the researchers wrote. Essentially, the lack of local news coverage led to the belief that officials would be worse stewards of the public dollar, so investors demanded higher interest rates.

This newsroom cataclysm occurred because Google and Facebook monopolized the digital ad market, hoovering up the revenue that used to support the journalism ecosystem. Currently, Google and Facebook receive 60 percent of digital ad revenue. Amazon and several other companies account for another 15 percent. That means every news publication in the country is fighting over, at best, 25 percent of the available ad revenue. In recent years, Google and Facebook have gained nearly all of the digital ad growth.[44]

Here is a quick look at how the two companies have used their monopolies to decimate the news industry:

The key mechanism underlying Google’s ability to dominate the digital ad market is that it largely controls how digital ads are bought and sold, inserting itself into the middle of transactions between advertisers and publishers and taking a cut that would otherwise go to those publishers.[45] Starting with its 2008 acquisition of DoubleClick, the corporation has rolled-up of much of the underlying infrastructure for buying and selling display ads. As Professor Fiona Scott Morton and David Dinielli put it, “Google has made it nearly impossible for publishers and advertisers to do business with each other except through Google.”[46]

Google ties its ad software to search data generated by the Google homepage and YouTube content – which is a must-have property for advertisers due to high engagement levels – plus the analytics systems that supposedly provide insights into how successful an ad campaign is. Its pricing is opaque, so publishers are not certain how large a cut Google is taking from them, other than that it’s significant, and advertisers are not certain that their ads are reaching the audience Google says they are.[47]

Google also directly competes against those publishers, since it too sells digital ad space. But it can use inside information gleaned from its ownership of the ad market infrastructure to front-run orders and to steer advertisers toward Google-owned properties such as YouTube.[48] [49] Publishers have little choice but to continue using Google’s services, because there are few other places to turn, and because Google’s data collection is so vast, and thus its targeting capabilities so extensive.

Google not only dominates the ad market, but also uses its dominance of search to directly hurt legitimate news outlets. For example, it demanded that news outlets adopt Accelerated Mobile Pages (AMP), under threat of exclusion from mobile search results, which it now loads for users rather than directing them to publishers’ websites. This keeps users within the Google ecosystem and hurts publishers’ ability to build an audience.[50] Publishers report lower ad revenue and lower traffic from AMP.[51]

Through its Google News and Google Discover apps, Google is also a news aggregator in its own right, providing sufficient content based off AMP pages that users often don’t have to leave for publishers’ sites, having gleaned the high points of the story they’re reading straight from Google.[52] (As noted above, fewer than half of Google queries now result in a click away from Google.)[53]

Finally, Google search is using news content in several ways that keep users in its ecosystem, such as providing “snippets” of articles in response to search queries that are sufficient enough information that users won’t move to the publishers’ site, or linking product review articles to its own Google sales platforms, so users can see the key parts of those reviews without leaving Google.[54] Those moves deprive publishers of traffic and insights into their audiences, which hurt their ability to build or monetize those audiences or generate higher traffic numbers in order to charge higher ad rates.

Facebook undermines the news industry via its own propensity for spreading misinformation and literal fake news against – stories concocted out of thin air by those hoping to profit from them. It serves as a breeding ground for local conspiracies, such as one falsely claiming Syrian refugees committed a rape in a small Idaho town (which had no Syrian refugees in it).[55] Against that content, it sells targeted advertising – collecting the revenue that could be keeping local news outlets, with editorial judgment and a wall between the content creators and advertising sales teams, in business.

Facebook’s business model is based, first, on its reach. It has more than 1.7 billion daily users worldwide, and also controls other key social network tools such as Instagram and WhatsApp that it acquired through mergers.[56] Facebook properties account for 75 percent of user time on social networks.[57]

Facebook gained that network using two methods. First, Facebook won more users than early competitors such as MySpace by pledging a safe space to both users and partners, promising it wouldn’t engage in the sort of data collection practices it currently employs across the web. Second, the corporation engaged in a merger spree to acquire competitors, most notably Instagram and WhatsApp.[58] Facebook, today, uses exclusionary practices, such as prohibiting interoperability with rival social media platforms, locking in users and enabling the corporation to exclude competitors from taking advantage of its networked scale. Switching from Facebook is only useful if your entire network of friends, family, and business and personal contacts move at the same time. As a result, the cost of switching away from Facebook to another network is high.

Facebook’s dominance enables it to collect significant amounts of personal data from both individuals and publishing partners. It can then target users with personalized ads, out-competing publishers by using their own audience data to enrich its ad targeting.

In 2018, the Pew Research Center reported that social media had surpassed local newspapers as a news source for Americans.[59] But Facebook’s newsfeed is designed to serve up sensational and rumor-laden content that encourages users to keep coming back for more – allowing Facebook to collect ever larger amounts of data, which it then uses to sell ever more targeted ads. By one estimate, Facebook controls 50 percent of available display ad space in the ad market.[60] Newspapers simply cannot achieve the reach or targeting capabilities for advertisers that Facebook can.

Then, adding insult to injury, Google and Facebook give a fraction of the money they’ve siphoned away from new outlets back to them in the form of grants that can never make up for what was lost.[61][62]

That dynamic leaves readers with fewer and fewer sources of real information able to sustain themselves, leaving local residents with less quality journalism on which to base their economic and democratic choices. Into that void have stepped hundreds of hyperpartisan sites pretending to be local news sources[63] – which, of course, have a large presence on Facebook.[64]

Facebook and Google Siphon Local Resources Away From Residents and Local Businesses:

Facebook and Google use the power they have amassed via their monopolies to prey on communities across America, offering jobs and investment in exchange for subsidies and other favors from local governments. Local officials desiring the investment large tech companies supposedly bring or who are cowed by the leverage they have – or who simply want to be associated with two of the largest, most recognized companies in the country – accede to their demands.

Facebook and Google are major beneficiaries of the tens of billions of dollars doled out by cities and states annually to businesses, having, respectively, received about $374 million and $882 million dating back to at least 2010 for Facebook and 2005 for Google.[65] Those amounts are just what has been disclosed, and are likely higher. They also benefit from reductions in utility costs unavailable to competitors.

Access to tax breaks, as well as cheaper land and utility costs, entrenches Google and Facebook’s power vis a vis their competitors, both nationally and locally, that aren’t able to negotiate the same terms with states and cities.

For instance, the local newspaper doesn’t receive the same terms from local governments, yet still competes with Google and Facebook in the digital ad market. Smaller firms hoping to enter businesses in which Google and Facebook operate, likewise, don’t receive the same levels of support from the state, making an already rigged competition even worse.

Subsidies for Data Centers

Much of the largesse the companies have received is for the massive data centers they need to keep their businesses running. Facebook received $150 million in subsidies for one such data center in Utah, and about $147 million for another in Texas.[66] Google received $360 million in subsidies for a data center in Oregon, and another $254 million for one in North Carolina.[67] Overall, Facebook has at least 12 domestic data centers in the U.S., while Google has at least 17.[68]

These subsidies hurt local communities in several ways. First, they siphon funds from local school budgets, because the subsidies usually come in the form of property tax reductions, and property taxes are the primary way in which American schools are funded.

In one instance in Altoona, Iowa, a tax assessor failed to note that a property tax exemption had been granted to Facebook, so the company’s taxes were included in the city’s budget, and then the school district’s budget. When the mistake was discovered, the school district lost $900,000 in funds, which an official said would have to be offset by spending cuts or by dipping into reserves meant for improvement projects.[69]

While the companies promote data centers as job creators for the local economy, they actually require very few workers, averaging just 30-50 jobs each.[70] There’s no evidence they lead to broader employment growth in a city or region.

Even with incentives, tech jobs are clustered around a few major American cities. [71] Rural communities pay hundreds of thousands of dollars for each tech job “created” through incentive programs.[72]

Utility Discounts

Facebook and Google strategically locate data centers near power sources, which makes sense, and is evidence they don’t need to be subsidized by the state. But in many instances, cities or states that have subsidized the companies’ proximity to that energy then give them a discount on the energy too, as well as water and other utilities. (Overall, 75 to 98 percent of incentives given to companies subsidize actions that would have been taken even in the absence of those subsidies.[73]) For example, Google received a 10 percent discount on its energy for one data center in Minnesota.[74]

The terms of those arrangements often aren’t made public, so the extent of the subsidies are opaque to the community. “We don’t know the amount of savings they are getting,” Gabriel Chan, a professor at the University of Minnesota, told Bloomberg Businessweek. “The state can go too far and give Google too much, but no one knows what the numbers are actually.”[75] To make up the difference, local utilities may turn to rate hikes on other customers.[76]

Facebook and Google Distort Local Democracy:

Many of the subsidies and discounts Google and Facebook receive are either not publicly disclosed or are hidden from public view by the corporations’ reliance on shell companies and nondisclosure agreements, disrupting the ability of local voters to hold the companies or elected officials accountable.

For instance, Google negotiated that rate discount in Minnesota through a shell company called Honey Crisp Power LLC. Similarly, in Midlothian, Texas, $10 million in tax breaks for a Google project was not disclosed until after the deal was formally approved by local officials. Instead, Sharka LLC, was the named beneficiary.[77]

As one professor put it, “Google has a strategic interest in getting their name out of these deals so that they go down more quietly, without public debate.”[78]

In a deal for a data center in Gallatin, Tennessee, Facebook went by the name “Project Woolhawk.”[79] Even when the Gallatin city council was voting on an economic development agreement between the city and the company, councilors did not disclose that Facebook was the beneficiary.[80]

Gallatin officials claimed to not know who the company behind Woolhawk was as the negotiations were ongoing. But even if they did, it’s possible they couldn’t disclose it because the company, along with Google and other big tech firms, demands local officials sign nondisclosure agreements when negotiating with them. [81]

The Partnership for Working Families used Freedom of Information Act requests to access eight such agreements officials signed with Google.[82] The documents prevent local officials from disclosing “the terms of any agreement entered into between the two parties, and the discussions, negotiations and proposals related thereto.”[83] In correspondence with a local official in San Jose, Google confirmed that the point of the NDAs was to prevent public relations problems in the community from the disclosure of details between the city and the company.[84]

Nondisclosure agreements also prevent the release of information regarding how much of a strain the companies put on local resources. One South Carolina agreement prevents the local water utility from disclosing anything about Google’s usage: “Google is not named, only an entry for ‘undisclosed customer’ appears with the usage amounts and price it paid left blank.”[85]

These tactics allow Google and Facebook to hide potentially deleterious effects on local communities and prevent local voters from holding office-holders accountable for the decisions they’ve made vis a vis the two companies.

Further compounding the problem, the economic development agreements between cities and Facebook and Google often include provisions requiring that the companies receive notification when Freedom of Information Act filings or other public records requests are made pertaining to those agreements, giving the companies time to formulate a response or attempt to quash the request.

Solutions

Reducing Facebook and Google’s harms at the local level requires both federal and local solutions. Federal policymakers must make structural changes to the companies’ business models, while state and local authorities need to refrain from granting the companies special privileges and introduce measures geared toward accountability and transparency.

- Reducing Google and Facebook’s dominance means changing the rules and laws that enable their business models. One way to start is through structural separations: For instance, splitting out Google’s general search from mapping or local reviews would disincentivize the company from self-preferencing its own content over those of its competitors, potentially improving local search tools and providing an opportunity for hyper-local search verticals to find traction. The Google-DoubleClick merger could also be reversed, as part of a series of breakups to return competition to the advertising tech market. The Facebook mergers with Instagram and WhatsApp could also be reversed, to bring more competition to the social media space.

- The Federal Trade Commission can write rules for dominant search engines prohibiting a variety of anti-competitive actions as unfair methods of competition under Section Five of the FTC Act. These include self-preferencing of search results, conditioning Google as a default search engine through the bundling of Android/Play on mobile devices, or payments to Apple in return for search positioning on iPhone’s Safari.

- Removing the liability shield they enjoy under Section 230 of the 1996 Telecommunications Act would put traditional publishers on a more even playing field and incentivize a form of advertising based on building trust with users, rather than on clickbait and sensationalism, by making the companies legally responsible for the content produced on their platforms. The eventual goal should be to abolish targeted advertising entirely.

- State attorneys general can join antitrust cases against Google and Facebook or initiate their own, particularly in the area of self-preferencing and tying of inferior products to those in markets which Google dominates. Attorneys general in more than 40 states are currently investigating Google alongside the federal government, though the exact contours of a future case are unknown. State attorneys general can also challenge acquisitions by the two companies, if federal antitrust enforcers won’t.

- States and localities can refrain from providing subsidies to the two companies. However, if that proves too difficult, as part of the rationale behind providing subsidies is that other states or cities will take advantage of a single state’s reticence to do so, states can join interstate compacts. Legislation introduced in 14 states would prevent using incentives to poach businesses from other states; a bolstered version that also disallowed the incentivizing of new businesses would prevent the subsidizing of Google and Facebook’s expansion. Congress could also use its power under the Commerce Clause to prevent states from using company-specific tax incentives[86] or could tie an abolition of such incentives to other federal funding.[87] If states choose to continue to use incentives, they should be targeted to local, smaller businesses.

- States could also use their powers to prevent city officials from entering into nondisclosure agreements with specific companies for the purposes of economic development and prevent their own economic development agencies from doing so. Or they could pass measures to ensure that all negotiations and materials pertaining to agreements with major corporations, as well as materials from any private entities that negotiate on behalf of state and local governments or development offices, are publicly posted. They could also force localities and school districts to abide by Governmental Accounting Standards Board statement 77, which requires disclosure of all corporate tax abatements, and which is not followed by many local governments.[88]

Conclusion

Facebook and Google’s power stems from the monopolies they’ve built in digital advertising. From that flows their ability to dictate terms to local communities, demanding benefits from small and mid-size cities that they don’t need, as well as secrecy that prevents local voters from holding the companies and their elected officials accountable. Their monopolies also harm local small businesses, who become collateral damage in the companies’ quest to undermine competitors in search and social. Dismantling those monopolies and promoting transparency and accountability at the local level will help build more resilient and equitable local economies and is crucial for maintaining the integrity of our democracy.